5 Famous Psychology Experiments

This article provides a brief overview of five of the most important, most influential, and most talked about psychology experiments in history.

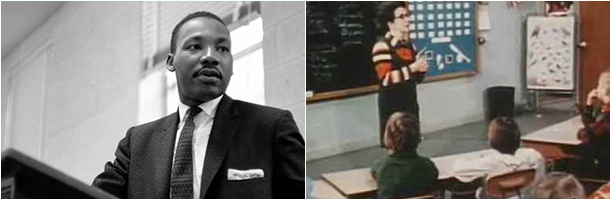

1) A Class Divided

The original diversity training

In 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., an elementary school teacher named Jane Elliott sought to help her all-white 3rd graders appreciate issues surrounding racism, bias, and prejudice. Frustrated with her attempts to get through to her students, who had limited contact with minorities, Elliott decided to do something both controversial and fascinating. She divided her class into two groups: blue-eyed children were treated as superior over the brown-eyed children for the first day. The next day, the preferential treatment was reversed. The exercise had a profound impact on many of the children, lasting well into their adult years. The story was recorded for the PBS series Frontline in an episode titled A Class Divided (1985). For a 1992 episode of Oprah, Elliott pretended to be a “brown-eyes supremacist” to highlight the absurd logic of racism. (The Oprah video is well worth 5 minutes of your time.)

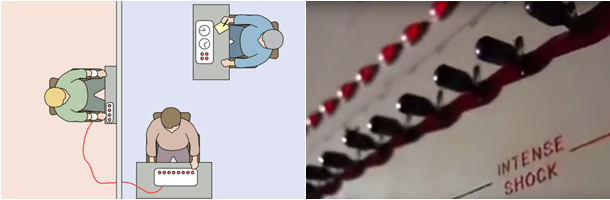

2) Milgram Experiment

Setting the conditions for good people to carry out evil

Concerned by Nazi war crimes and the Nuremberg defense (“only following orders”), Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram designed a series of dramatic experiments in the 1960s to test people’s obedience to authority. Under the direction of a supervisor, a volunteer would be instructed to give an electrical shock to another volunteer (actually an actor) each time a question was answered incorrectly. To see how far people would go, the shocks would gradually escalate to the point of being life-threatening. Despite Milgram’s expectation that only a small percentage of volunteers would proceed to the maximum voltage — and even though the actor could be heard screaming and pleading with the volunteer to stop — 65% followed their orders to the very end. Milgram’s work is not without its critics.

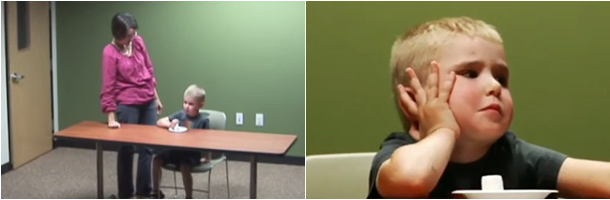

3) The Marshmallow Test

Exploring the link between self-control and success

In 1972, Stanford professor Walter Mischel placed children one by one alone in a room with a marshmallow sitting on a table in plain sight. The children, aged four to six, were told by the experimenter that they could have a second marshmallow when he returned from an errand (about 15 minutes) — but only if the child didn’t eat the first marshmallow. The same children were later tracked down in high school. Apart from being generally better socially and psychologically adjusted, those who had waited longest to grab the confectionary had an average score of 210 points higher on their SAT results than the kids who grabbed fastest. This was one of the first major experiments to suggest that impulse control has important implications for long-term individual achievement. (You will love the video showing kids' reactions when left alone with the marshmallow.)

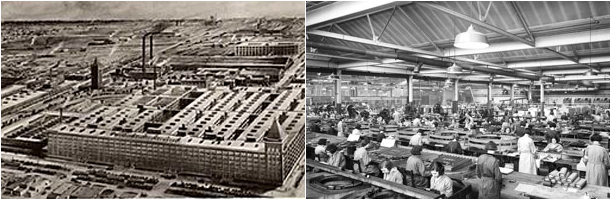

4) Hawthorne Effect

The mere act of studying people can influence their behaviour

A telephone equipment factory called Hawthorne Works commissioned a series of studies through 1924-32 to evaluate (among other factors) the effect of lighting on worker performance. Changes in light intensity, regardless of the particulars (e.g., low level to high level or high level to low level) produced temporary increases in productivity, but curiously these gains ended shortly after the experiment wrapped up. After controlling for variables, it was eventually proposed that the temporary boost in output was the result of the workers’ inclusion in the study (i.e. the novelty of being given attention, being involved in attempts to improve workplace conditions, etc). The Hawthorne Effect is often referenced in business and academic research, viewed as having important implications for study design and evaluation.

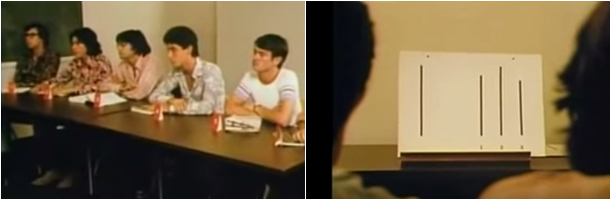

5) Asch Conformity Experiments

Testing the limits of peer pressure

During the 1950s, Dr. Solomon Asch found creative ways to put people’s fear of being different from the majority to the ultimate test. In the classic experiment, participants were asked to match the length of a vertical black line (on the left) to one of three options (on the right) as part of a “vision test.” On some of the trials, several actors in the group would provide answers that were clearly wrong. When it came to the one real participant in the group, the answer given was often in agreement with the consensus (about 37% of the time) — despite the evidence of their error right in front of their eyes. In another famous experiment (video below) inspired by Asch’s work, an elevator is loaded with a group of actors facing the wrong direction. In many cases, test subjects enter the lift and adjust their behaviour to match the group, hilariously forfeiting their individuality and better judgment to the so-called “wisdom of the crowd.”

Topics:

Psychology

Theo Winter

Client Services Manager, Writer & Researcher. Theo is one of the youngest professionals in the world to earn an accreditation in TTI Success Insight's suite of psychometric assessments. For more than a decade, he worked with hundreds of HR, L&D and OD professionals and consultants to improve engagement, performance and emotional intelligence of leaders and their teams. He authored the book "40 Must-Know Business Models for People Leaders."

.png?width=374&name=Nutshell%20-%20Big%205%20Personality%20Traits%20(OCEAN%20Model).png)

We Would Like to Hear From You (0 Comments)