Smarter Thinking: The Socratic Method

Just as the scientific method is one of the most prominent tools associated with science, the Socratic method is one of the foremost tools associated with critical thinking. This article is part of the Smarter Thinking Series, which includes a range of mental models and tools to improve general decision making, business acumen, and critical thinking.

Background

The technique is named after Socrates (469-399 BC), one of the most influential philosophers in history, who lived in ancient Athens, Greece. There are no known writings produced by Socrates. Most of what we know about his life comes from Plato, a student of Socrates, who wrote a series of “dialogues” featuring his teacher (although Socrates did not consider himself a “teacher” in the formal sense).

As told in Plato’s Apology, we learn that the Oracle of Delphi has confirmed to a friend of Socrates that no man is wiser than Socrates. Disturbed after hearing this news, Socrates sets out on a journey to understand how this could be, since he does not consider himself to be wise whatsoever. The philosopher travels around the city, seeking out respected Athenians — including politicians, poets, and artisans — who he suspects are wise about moral matters, such as the nature of virtue, courage, or justice. However, when the experts’ beliefs are cross-examined under his inquisitive, skilful, and persistent questioning style, he finds they are unwilling to admit that they do not really know what they suppose. What makes him wiser than others, Socrates concludes, is his willingness to acknowledge the true extent of his own ignorance. Socrates’ spate of dialogues eventually leads to him being charged with corrupting the minds of the youth and “impiety,” which famously results in Socrates committing suicide by drinking hemlock, despite having the apparent opportunity to escape his death sentence with the help of friends.

Even though its roots are some 2,500 years old, and other problem solving, coaching, and questioning techniques have since arrived on the scene (e.g., Root Cause Analysis, 5 Whys, GROW, 6 Thinking Hats), the Socratic method still remains an extremely popular mental model. It is widely used by teachers, law professors, facilitators, consultants, coaches, and therapists.

Gregory Vlastos, one of the 20th century’s most influential scholars on ancient philosophy, regarded the Socratic method as among the greatest achievements of humanity.

Definition

The Socratic method is variously defined as a “pedagogical technique,” “a teaching style,” “a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue,” “a form of dialogic discussion,” “a form of inquiry and debate,” “a method of inquiry and instruction,” and “a disciplined form of questioning.” There is no “official” version of the method, universal definition, or universally accepted structure, framework, methodology, step-by-step process, or standardised set of questions.

Overview

The Socratic method is used in a variety of ways and with a variety of aims. In its loosest sense, the Socratic method has come to mean almost any teaching method involving question and answer, in contrast to teaching in the form of lecture (Scott, 2004). There is a long history of academic debate over whether Socrates really has a method, or whether he has a number of methods, and — if he only has one — what elements are most characteristic. Scholars and historians who have closely examined Plato’s dialogues see a wide range of discrepancies in how Socrates engages in conversation, and find it very difficult to regard Socrates as having any single uniform approach, even at a very broad level. The influential work of Gregory Vlastos advanced the idea that Socrates has a method, which Vlastos dubbed “the Socratic elenchus,” however this view has been disputed by many accounts.

The Socratic method, according to one prominent view, is a method of hypothesis elimination. The questioner is presented with an assertion or hypothesis by an interlocutor. The questioner proceeds to cross-examine the hypothesis by a persistent and targeted line of questioning, with a view to exposing a contradiction or weakness. If a weakness is discovered, the hypothesis may be eliminated. After discarding a faulty hypothesis, a new or reformulated hypothesis may be suggested, and the process repeated. The Socratic method, in this sense, is less a model for problem solving than it is a model for critical thinking, diagnostically probing intuitions, assumptions, or beliefs, and testing their validity. A considerate, non-judgmental, non-confrontational attitude is often seen as an important part of the process. Other key features of the method that have been proposed include an emphasis on intellectual humility, uncertainty, cooperation, curiosity, and shared learning. Socratic questioning is most often used between two or more people, but it may also be used on one’s own.

3 Major Versions of the Socratic Method

Depending on the context, the term “Socratic method” may refer to a style of questioning reminiscent of Socrates; reminiscent of a teaching mode commonly used in modern primary and secondary education; reminiscent of a teaching mode used by some U.S. law professors; or some combination thereof.

1. “Classic” Method (Socrates)

Although Socrates does not appear to have a consistent or unified method that is apparent throughout Plato’s writings, he would often start a dialogue by professing his ignorance on a philosophical subject (e.g., “What is courage?”) and request someone to propose true knowledge (e.g., “Courage is endurance of the soul”). Socrates would then reveal flaws in a given definition or claim, usually by providing a counterexample or competing definition, and — after inducing much confusion and perplexity (a mental state known to the Greeks as “aporia”) — people would be forced to confront their own ignorance.

Some of the distinctive characteristics of the “classic” Socratic method are:

- Uncertainty or “Aporia” (doubt, ambiguity, ignorance, or uncertainty is expressed or considered)

- Moral Inquiry or “Ethics” (discussion is focused on moral matters i.e., how to live a good life)

- Logical Refutation or “Elenchus” (beliefs, principles, or assumptions are cross-examined)

2. “Modern” Method (Primary & Secondary Education)

The “modern” Socratic method is most often associated with teaching in the context of primary and secondary school, whereby the teacher has a curriculum or “knowledge agenda” and uses a series of probing and leading questions to draw out thoughts from the student in order to guide the student to the correct answer, or simply help him/her see things in a different light. The “modern” method is so named, not because it is recent in invention, but because of its prominence in modern education (Maxwell, 2015). Socrates’ “switch” to this method can be seen in the dialogue Meno, in which he helps a slave boy calculate the lengths and area of a square.

Some of the distinctive characteristics of the “modern” Socratic method are:

- Knowledge Agenda (the teacher usually has specific learning outcomes and withholds answers)

- Guiding (the teacher seeks to build knowledge by guiding the student)

- Developmental (the teacher is concerned with developing the student’s reasoning skills)

3. “Socratic” Case Method (Legal Education)

The “Socratic method” has been called a “defining element of American legal education.” According to a 1996 survey, the method was used by 97% of law professors with their first-year classes, although more recent accounts suggest a decline in its use and popularity. The term “Socratic method,” when it appears in the context of legal education, is not necessarily indicative of the descriptions given so far. Elements of Socratic teaching are often combined with the “case method” (as made famous by Harvard). Law students in many U.S. universities are required to read up on case summaries prior to attending class. Once in session, the professor may “cold call” (pick a student at random) and begin grilling the student on the details of the case, testing his/her responses from a number of angles. The intimidation, fear, and stress created through the use of this technique (like that seen in the 1973 film The Paper Chase) has been the subject of much criticism, and its emphasis on superficial fact checking rather than shared inquiry has led some to dispute whether this version of the method is truly “Socratic.”

Further Perspectives

- Richmond et al. (2016) describe the Socratic method as being exemplified by 1) questioning knowledge, 2) evaluating knowledge, 3) having regard for self-generated knowledge, and 4) focusing on error to evoke doubt.

- Paul and Elder (2007) identify at least two major purposes of Socratic questioning in teaching: 1) Helping students distinguish what they know from what they don’t, and 2) Helping students acquire Socratic tools to apply in everyday life

- Boghossian (2012) identifies five steps in the Socratic approach: 1) Wonder, 2) Hypothesis, 3) Elenchus (refutation and cross-examination), 4) Acceptance/rejection of the hypothesis, and 5) Action.

- Lam (2011) identifies four key steps in the Socratic method: 1) eliciting relevant preconceptions, 2) clarifying preconceptions, 3) testing one’s own hypotheses or encountered propositions, and 4) deciding whether to accept the hypotheses or propositions.

- Cain (2007) identifies three main ways of using the method in Socrates’ philosophical discourse: 1) refutation, 2) truth-seeking, and 3) persuasion.

- Peterson (2009) provides six Socratic elements that can be incorporated into the decision making process by a manager: 1) Ask an individual to provide instances or justifications for the position advocated, 2) Interject a counter-example in response, 3) Ask whether anyone in the group agrees with the position advocated, 4) Suggest a parallel example, 5) Illuminate a specific concept or position using an analogy, and 6) Play the role of devil’s advocate to an articulated position.

Socratic Method

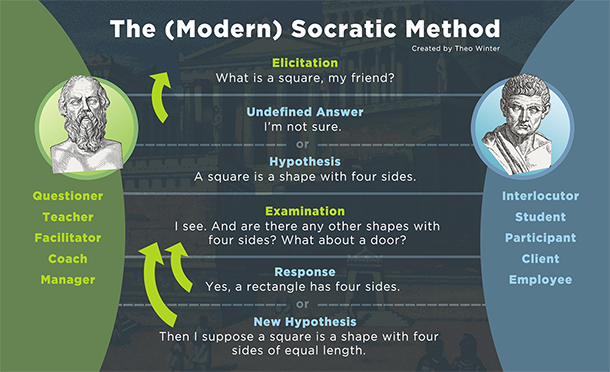

One way of depicting the modern Socratic method is shown below.

In the diagram shown, the questioner initiates the Socratic method by attempting to elicit a clear hypothesis from the interlocutor. If a clear hypothesis is not produced, the questioner may attempt to rephrase the question, or offer a different suggestion. Once the interlocutor affirms a hypothesis, the questioner can begin examination. The questioner may seek to understand why the interlocutor made that decision; ask for evidence or reasoning to support the hypothesis; ask for thoughts on a counter example or a differing perspective, etc. After the initial examination, the interlocutor has a chance to respond (agree, disagree, clarify, elucidate, etc.) — or they may simply decide to revise their hypothesis. When a new hypothesis or a response is given, the questioner may again present further examination questions. The response stage can involve a lengthy question-and-answer exchange: the questioner may spend time probing different aspects of reasoning; guide the interlocutor towards an alternative view; the interlocutor may provide a counter response to the examination that the questioner is satisfied or unsatisfied with, etc. The entire dialogue may last a few seconds or several hours, depending on its aim, nature, and the participants' personalities, and may end with or without the interlocutor revising the hypothesis.

Note: The model above is intended as general guide for understanding, and is not a strict prescriptive process.

Socratic Questions

Richard Paul (1993) outlines six types of Socratic questions, which are often cited as a teaching resource.

1. Clarification

- What do you mean by ___?

- Could you rephrase your point?

- Why do you say that?

2. Probing Assumptions

- What being assumed?

- Is that assumption sound?

- Could the assumption be different?

3. Probing Reasons and Evidence

- How do you know?

- What is the quality of the evidence?

- Are there any reasons to doubt that?

4. Viewpoints or Perspectives

- How might other people approach it?

- What is an alternative view?

- Have all the alternatives been considered?

5. Implications and Consequences

- What is the result?

- What does that imply?

- If ___ is true, how does it affect ___ ?

6. Questions About the Question

- Is answering this question useful?

- Do we properly understand the question?

- How could we resolve this question?

Benefits, Advantages and Strengths of the Socratic Method

Some of the commonly cited benefits of the Socratic method include:- Alternative to telling/selling/lecturing

- Cooperative: Focused on dialogue rather than argument

- Persuasive: a good technique to create doubt or “soften” a position, if not change it

- Open, inclusive, and non-hierarchical

- Does not require special qualifications, experience, or materials

- Popular and generally well accepted pedagogical technique

- Applicability: Can be incorporated into a wide range of fields, situations, and contexts

- Flexibility: Approaches can be easily adapted/modified

- Availability of literature, articles, and resources

- Encourages critical thinking

- Encourages intellectual humility

- Encourages active mental engagement

- The act of speaking/articulating an argument may reveal overlooked flaws

- Potential argument flaws may be assessed in advanced, more often, and more deeply

- Connects to an interesting story/important historical figure (i.e., Socrates)

Criticisms, Limitations and Weaknesses of the Socratic Method

Some of the commonly cited criticisms of the Socratic method include:

- Lack of empirical research / controlled studies

- Absence of central authorship: No definitive conceptual framework

- Proliferation of approaches and interpretations

- Time consuming

- Limited scope of content can be handled/covered

- Cognitively focused rather than behavioural/experiential

- Ineffective for skill transfer, especially complex/specialised (e.g., how to code, draw, swim)

- Ease of use/popularity may lead to over-reliance and neglect of other techniques

- Mentally demanding, especially for the interlocutor

- Relies largely on the cognitive skills of the questioner to direct discussion and detect logical errors

- No inherent structure to avoid reaching “false positive” or “false negative” conclusions

- May be used dishonestly/unethically to seed doubt

- “Downward” focus on definitions/evidence may ignore applications/broader relationships

- May cause discomfort/stress for the interlocutor, especially in a large group setting

- Inappropriate for very young children

Topics:

Smarter Thinking

Theo Winter

Client Services Manager, Writer & Researcher. Theo is one of the youngest professionals in the world to earn an accreditation in TTI Success Insight's suite of psychometric assessments. For more than a decade, he worked with hundreds of HR, L&D and OD professionals and consultants to improve engagement, performance and emotional intelligence of leaders and their teams. He authored the book "40 Must-Know Business Models for People Leaders."

/Maslows%20Hierarchy_%206%20myths.png?width=374&name=Maslows%20Hierarchy_%206%20myths.png)

We Would Like to Hear From You (0 Comments)