The Main Cause of Job Stress is Not What You Expect

Who has more stress? A CEO or an Administrator? You might think the CEO has more to worry about, and that's a reasonable assumption. After all, those who occupy the most senior positions are required to shoulder greater responsibilities than those in administration or support roles.

The assumption is: more responsibilities = greater stress.

If like most people, this assumption rings true for you, then your gut is missing a crucial piece of information: The demands of a job are only one part of the picture, and not in and of themselves the major cause of stress-related illness. So what is the major cause?

Decades of research have now clearly isolated the culprit: it’s the combination of high demands and low control.

So during times of change, particularly this period we're experiencing with Covid-19 restrictions, we have low control over the situation. Many people will have adapted to the demands of their professional (and/or family) role, but when the shots are being called by someone else, stress can ensue.

This combination — high demands and low control — more than anything else, creates the perfect catalyst for destroying the health of your workforce. The more powerless you feel, the more stress hormones in your bloodstream will tend to rise. The more stress hormones are increased, the greater the wear and tear on your body. Persistent stress leads to impairment of the immune system, which makes you more susceptible to illness and death.

Stress may escalate fast so it needs to be appropriately addressed quickly. The perception of psychological control is key in responding to stress.

Supporting Research

In 1967, a landmark study was undertaken by the UK government, which would later become known as the first Whitehall study (i.e. Whitehall I). This 10-year study examined the health of 18,000 males aged between 20 and 64, who were employed in the British civil service. Because public servants in the UK work in a highly stratified employment hierarchy and all receive the same level of health care, it makes the perfect scientific testing ground for determining the types of environmental factors that have the most significant impact on employees’ health and well-being.

Whitehall I identified a link between hierarchical status and mortality, in particular from cardiovascular disease. The results were conclusive: the less senior an individual was in the employment hierarchy, the shorter the life expectancy.

The second Whitehall study (i.e. Whitehall II) was launched in 1985. This study examined over 10,000 civil servants aged between 35 and 55 (two-thirds male and one-thirds female), with the first phase of research completed in 1988.

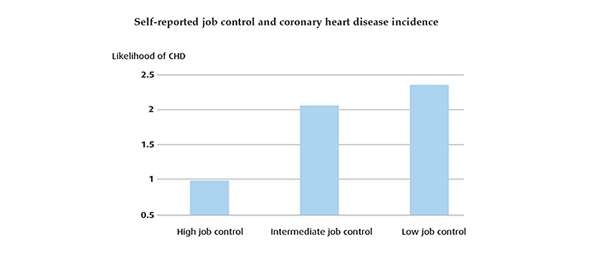

Whitehall II showed the same social-mortality gradient in women as well as men from the first study. Crucially, the data from Whitehall II confirmed that it is the combination of high job demands and low control that is the major cause of stress-related illness.

Above: Data from the Whitehall II study (Marmot et al., 2004). People with intermediate or low job control had over twice the incidence of coronary heart disease as people with high job control.

Above: Data from the Whitehall II study (Marmot et al., 2004). People with intermediate or low job control had over twice the incidence of coronary heart disease as people with high job control.

This hierarchy “death slope” not only applies to humans! Stanford neurobiologist, Robert Sapolsky, has conducted over 20 years of research on baboons and was the first to validate the findings of the Whitehall studies in another primate species. Again, this runs counter to many people’s basic intuitions.

Alpha males are not only responsible for protecting the group from predators and rival troops, but must also deal with internal competition from younger males. (You would think that’s got to be more stressful than being one of the gang!) Yet the research clearly shows that high-ranking baboons in a stable dominance hierarchy have lower stress-hormone levels than their subordinates.

Above: Robert Sapolsky, as featured in the 2008 National Geographic documentary, "Stress: Portrait of a Killer."

Above: Robert Sapolsky, as featured in the 2008 National Geographic documentary, "Stress: Portrait of a Killer."

Many researchers and writers describe autonomy, freedom and self-direction as basic human needs. What most people in the workplace may not realise, however, is that a fundamental lack of control in their jobs is — quite literally — killing them.

As if you didn’t already have enough to worry about this week…

Measuring Low Control in the Stress Quotient

Our tool, the Stress Quotient, measures 7 core stress hotspots and 17 sub-factors that have the potential to contribute to an individual’s overall stress in the workplace. The 7 core factors collectively represent the most common, universal causes of stress in the workplace, and the 17 sub-factors allow team members to easily identify and target the areas of most concern.

One of the 7 core factors is the Control Index, which is tied to issues related to the degree of influence and authority, both formal and informal, over the work. A high score on the Control Index is likely to occur when there is an absence of autonomy, freedom and power to affect how the work is done.

Since it may be helpful for individuals and teams experiencing a change or loss of control related to the Covid-19 restrictions, we have partnered with our supplier TTI Success Insights (ANZ) to offer complimentary Stress Quotient assessments in 2021 and 2022 (with a limited number per organisation). Simply email our team at hello@dtssydney.com to request more information and/or a complimentary assessment. We're here to help.

Since it may be helpful for individuals and teams experiencing a change or loss of control related to the Covid-19 restrictions, we have partnered with our supplier TTI Success Insights (ANZ) to offer complimentary Stress Quotient assessments in 2021 and 2022 (with a limited number per organisation). Simply email our team at hello@dtssydney.com to request more information and/or a complimentary assessment. We're here to help.

In the meantime, download the Stress Quotient Infographic.

Note: This blog post was originally shared in May 2016, and it was refreshed and republished in July 2021 with up to date information and context.

Theo Winter

Client Services Manager, Writer & Researcher. Theo is one of the youngest professionals in the world to earn an accreditation in TTI Success Insight's suite of psychometric assessments. For more than a decade, he worked with hundreds of HR, L&D and OD professionals and consultants to improve engagement, performance and emotional intelligence of leaders and their teams. He authored the book "40 Must-Know Business Models for People Leaders."

.png?width=374&name=The%20Stress%20Chronicles%20(Part%201).png)

/how%20netflix%20reinvented%20%20hr.png?width=374&name=how%20netflix%20reinvented%20%20hr.png)

We Would Like to Hear From You (1 Comment)