The Perils of Complexity & Cognitive Bias

"There is no polite way to put it: we are not as smart as we think we are. We are irrational, illogical, innumerate, unreasonable and overreactive... our two biggest problems — the most prominent (and interesting) of our cognitive frailties — are oversimplification and overconfidence." — Ted Cadsby, Closing the Mind Gap

The world we awaken to is scary, complex, and confusing. Because we’re not sure what the hell is going on as children, we crave answers.

Why is the sky blue? How do fish breathe underwater? What is electricity? Why are dogs so cuddly? Why isn’t 11 pronounced onety one? Mum? MUUUUUM?!

In our quest to understand the nature of reality, the questions will, at some point, sooner or later, proceed towards the most basic and personal.

Why am I here? What is the purpose of my life? How should I live?

Good news: It’s not a choice between life A and life B. There are hundreds of culturally constructed political systems, philosophical creeds, economic theories, ideological doctrines, and societal structures, multiplied by countless thoughts and observations that have been spawned over the centuries by philosophers, prophets, poets, rulers, revolutionaries, pundits, journalists, writers, speakers, scientists, educators, and entertainers.

Bad news: That's more ideas than any single person will ever have time to study.

And, let’s be honest, that doesn’t really bother us.

As a species, we're not exactly known for our love of complexity.

The general public's lack of appetite for basic scientific knowledge is well documented and, frankly, a little terrifying. For example, a couple of years back the Australian Academy of Science surveyed around 1,500 people and found that more than 40% of Australians do not know how long it takes for the Earth to travel around the sun (365 days).

Without baseline factual knowledge, how can citizens begin to make well-informed decisions on public policy such as climate change or nuclear power? Framed another way, how can parents make good health choices for their kids at the supermarket if they don't know how to read nutritional labels?

The other week I was reading an article in a general publication that included the formula f=ma (Newton’s second law of motion) — force (f) = mass (m) x acceleration (a) — which reminded me of a warning that Stephen Hawking was once given by his book editor: for each equation included, it would halve sales. It's hard to imagine a piece of PR advice for a theoretical physicist that is simultaneously more practical and depressing.

Disinterest in science or math isn't necessarily the root problem, nor our general approach to education, though much could be improved. The fundamental problem, one that has very meaningful consequences for the fate of the human race, concerns the gap between the primitive infrastructure of the brain and the "smarts" required to navigate our fantastically complex global world—a gap that is growing wider and wider.

"The real problem of humanity... we have Palaeolithic emotions; medieval institutions; and godlike technology."— E. O. Wilson

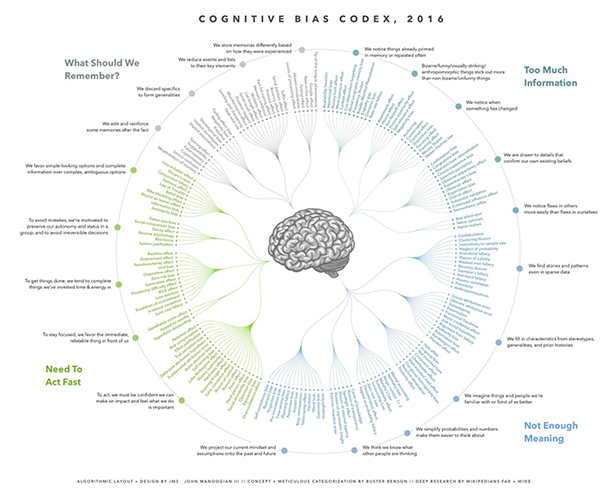

Humanity's mission is clear and present: we are gonna, to quote Matt Damon's character in The Martian, "have to science the shit out of this." Yet, the greatest enemy we face is not ourselves, at least not as a separate and oftentimes competing tribes, but rather our selves: our part god, part monkey brains. The evolutionary "hard-wiring" of the three-pound squishy supercomputer between our ears has given rise to a brilliant and devious array of systematic decision-making shortcuts and pattern filters known as cognitive biases.

The chart shows some of the hundreds of cognitive biases that have been identified. See more

Feeding into this picture is an important mental tendency called black and white thinking.

It's much easier to engage with the world when we are able to sort things into simple dichotomous categories like always and never; yes and no; on and off; true and false; good and bad. If a dog bites us as a toddler, all dogs are bad. DOGS = EVIL DEMON MONSTERS. This extreme labelling might save our life later if we happen to see another dog passing by and take cover under a bush. Only later do we learn of the existence of different types of dogs and start to revise our stereotype. Some dogs are big, some have brown fur, some drool too much, some are mean and bite, others are playful and fun. And some dogs are mean and fun.

This is belief nuance—beliefs that start to approach the complexity of reality.

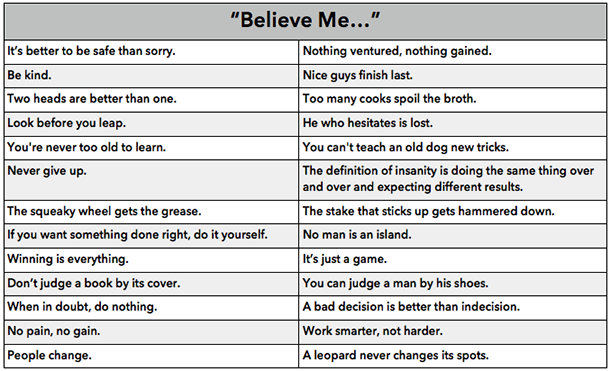

Consider the following table of statements, which continues a venerable and centuries-long tradition of humans condensing complex social dynamics into manageable, bite-sized rules of engagement.

Though well-intentioned, many of these statements offer a false dichotomy. (The appearance of only two options when more exist.)

For example, the American idiom “the squeaky wheel gets the grease” is often used in business to remind people that if they’re loud and vocal about a problem, they’ll get the necessary attention to have it solved, whereas if you’re too timid or quiet, you’ll be ignored. The Japanese have precisely the opposite proverb: “The stake that sticks up gets hammered down,” meaning that if you make too much noise and stand out you will be subject to criticism.

Even if you do live in America, "the squeaky wheel" advice can still lead to bad decisions. In one situation, it might be a good idea to complain to the restaurant manager about the poor service and be the recipient of a free meal. In another situation, you might be eating with a new boss and several important clients and find yourself being silently judged as rude and obnoxious, which could cost you a promotion.

As adults, we might intellectually understand that the world is complex, but still find ourselves drawn to using black and white language:

- “All politicians are crooks.”

- “CFOs only care about the bottom line.”

- “Customers will never buy from organisations they don’t trust.”

- “Goal-setting is absolutely essential to success.”

- “You can achieve anything you set your mind to.”

For many, and I include myself as a habitual offender, suspect generalisations can easily sneak their way into everyday conversations. Sometimes it’s more the basic sentiment in communication that counts. Too much focus on semantics can make you seem like a pedantic jerk. Too little focus and you don't know what the hell someone is talking about. I am prone to letting lazy generalisations creep into my sentences to simplify ideas and often run the risk of oversimplifying. The onus remains on me as the storyteller to mind the balance—between complexity and simplification—to make sure whatever idea I'm "getting at" is not misinterpreted. And I have failed miserably plenty of times. (But, I mean, give me a break. Words are hard, dude.)

Like you, I am a prisoner of my experience—someone holding a small cup of knowledge in a vast and overwhelming ocean of data. The antidote, or at least partial defence, that I have found invaluable for combating my complexity anxiety and knee-jerk bias is critical thinking.

Critical thinking is not watered-down pessimism, reckless criticism, or the indiscriminate dismissal of ideas, but suspending judgment and taking time to examine things rationally, rather than automatically jumping to a conclusion, taking sides, or putting forward an opinion that you then feel an irrational internal pressure to defend against your peer group.

But that's a whole 'nother topic I'll need to explore in a "part 2" article. If you're keen to continue learning about critical thinking and cognitive biases, I highly recommend Farnam Street, in particular The Baloney Detection Kit: A Summary of Critical Thinking.

Topics:

Smarter Thinking

Theo Winter

Client Services Manager, Writer & Researcher. Theo is one of the youngest professionals in the world to earn an accreditation in TTI Success Insight's suite of psychometric assessments. For more than a decade, he worked with hundreds of HR, L&D and OD professionals and consultants to improve engagement, performance and emotional intelligence of leaders and their teams. He authored the book "40 Must-Know Business Models for People Leaders."

/30%20Statistics%20On%20Emotional%20Intelligence.png?width=374&name=30%20Statistics%20On%20Emotional%20Intelligence.png)

/30%20Statistics%20On%20Recruitment%20%26%20Retention.png?width=374&name=30%20Statistics%20On%20Recruitment%20%26%20Retention.png)

We Would Like to Hear From You (0 Comments)